Pancreatic Cancer

Pancreatic Cancer Q & A

The pancreas is an organ which lies behind the stomach. It is anatomically divided into the head, neck, body and tail.

It has two major roles – the control of blood sugar by producing insulin and food digestion by producing digestive enzymes.

Pancreatic cancer (pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma) arises from the part of the pancreas that produces digestive enzymes (the exocrine part).

This is different from tumours that occur in the part that produces hormones such as insulin (the endocrine part).

Pancreatic cancer is the ninth commonest cancer affecting just over 8000 people in the UK each year.

It is not clear what causes pancreatic cancer. Some of the risk factors include smoking and chronic (prolonged) inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis).

Excessive alcohol intake is a common cause of pancreatitis. Familial pancreatitis and certain familial cancers of the breast and bowel are also associated with a higher risk.

The symptoms depend on the location on the cancer. When the cancer is in the pancreatic head, which is the commonest site for cancer, it can block the bile duct, causing jaundice (yellowing of the skin), dark urine, pale stools, and itchy skin.

When the cancer obstructs the pancreatic duct, it prevents the flow of digestive enzymes, resulting in an inability to digest fat in food. This leads to bulky offensive stools that are difficult to flush. The inability to digest food effectively causes weight loss.

There may also be abdominal or back pain, nausea and loss of appetite. Some patients may present with symptoms of diabetes. Cancer in the body and tail of pancreas usually causes abdominal or back pain and weight loss.

Unfortunately most pancreatic cancers present at an advanced stage. Occasionally pancreatic tumours are picked up on a scan which is done for another reason.

Blood tests are usually performed to confirm the presence of jaundice. This is followed by an ultrasound scan and a computerised tomography (CT) scan. Occasionally a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan is performed.

In most cases, it is necessary to obtain a small sample of tissue (biopsy) from the pancreas to confirm the diagnosis. If jaundice is present, then this often needs to be treated by draining the bile duct.

This is done by a procedure called endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which involves passing a flexible tube (endoscope) through the mouth. The endoscope is used to obtain samples from the tumour and to place a plastic tube (stent) to help drain the bile across the site of the blockage. Tissue from the tumour can be obtained at the same time.

Another procedure that can be used to obtain tissue samples is endoscopic ultrasound. This involves using a flexible endoscope with an ultrasound probe at the end, which allows a close examination of the pancreas and maps out the relation of the tumour to major blood vessels in the vicinity. A fine hollow needle is used to extract a biopsy from the tumor to confirm the diagnosis.

For every 100 patients with cancer of the pancreas, less than 20 can have their cancer surgically removed. In the rest the cancer is too advanced for surgery to be beneficial.

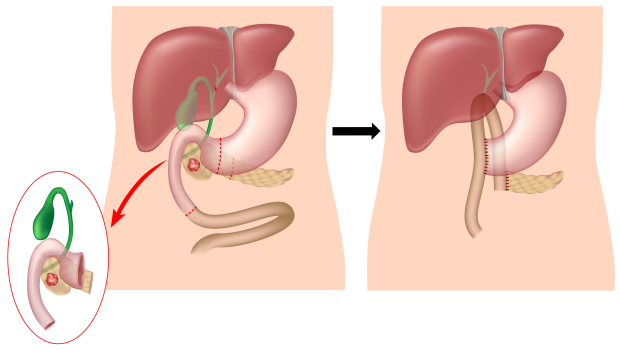

Whipple’s operation (pancreatico-duodenectomy) is usually performed to remove tumours in the head of pancreas (the operation is also performed for cancers arising in and around the ampulla, distal bile duct and duodenum).

This involves the removal of the pancreatic head together with the duodenum (the first part of the small bowel) and a short length of stomach and small bowel. The gallbladder and part of the bile duct are also removed.

The remaining pancreas, the bile duct and stomach are then connected to the small bowel to restore the gastro-intestinal continuity. This complex operation usually requires a hospital stay of 1-2 weeks.

The Whipple’s Procedure:

Tumours arising in the body or tail of the pancreas are removed by an operation called distal pancreatectomy which usually involves removal of the spleen (splenectomy) as well as the part of pancreas affected by the tumour.

Chemotherapy is recommended after surgery in most cases. This may be as part of a clinical trial testing different regimens of chemotherapy.

Radiotherapy in combination with chemotherapy is occasionally used to shrink advanced tumours that have not spread.

Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumours

Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumours Q & A

Pancreatic NETs (or islet cell tumours) arise from the endocrine cells of the pancreas. Endocrine cells are responsible for producing hormones such as insulin. Some of these tumours produce hormones that are released in the blood and cause symptoms. These are known as functioning tumours and take their name from the hormone they produce. Below is a list of some of these tumours:

- Insulinomas produce insulin

- Gastrinomas produce gastrin

- Glucagonomas produce glucagon

- Somatostatinomas produce somatostatin

- VIPomas produce Vasoactive Intestinal Peptide (VIP)

Pancreatic NETs are rare. They account for only one in 20 pancreatic tumours. About a third are functioning tumours and are more likely to be benign.

The remainder are non-functioning and more likely to be malignant.

Functioning pancreatic NETs present with symptoms relating to the excess hormone production:

- Insulinomas present with low blood sugar (hypoglycaemia) causing ‘funny turns’ or even fits.

- Gastrinomas present with stomach ulcers.

- Glucagonomas present with diabetes.

- Somatostatinomas present with gallstones, inability to digest fats and diabetes.

- VIPomas present with diarrhoea.

Some NETs are found incidentally on scans performed for other reasons or because of symptoms related to their spread to the liver.

Initially blood tests are performed to test for the presence of hormones and other peptides (chemicals) produced by the tumour. A gut hormone profile includes glucagon, gastrin, VIP and somatastatin. The proteins chromogranin A and B are also measured.

A combination of scans may be needed to localize the tumour and determine its size and whether there is more than one, as well as checking whether there is any spread to other organs. This may include a triple phase computerised tomography (CT) scan, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan and an endoscopic ultrasound.

Most NETs have receptors to the hormone somatostatin. These receptors are structures on the surface of the tumour that bind to somatostatin and a structurally similar chemical called octreotide. Octreotide is used in a test called OctreoScan, which detects any tumours in the body that have somtaostatin receptors.

In this test, octreotide is ‘labelled’ with a substance that contains a very small amount of radioactivity (this decays naturally in the body) and is injected into a vein. The ‘labelled’ octreotide binds to tumours and can be detected by a scanner. In this way the size and spread of NETs can be assessed. Radio-labelled octreotide can also be used to treat NETs.

Surgery offers the opportunity of cure in some cases. Pancreatic operations performed for NETs may be less extensive than those for pancreatic cancer (adenocarcinoma). In some cases it may be possible to remove the tumour with very little surrounding pancreas (enucleation).

Octreotide or similar drugs can be given for symptomatic tumours not amenable to surgery. They controls symptoms by reducing the release of hormones by the tumour and may slow down its growth.

Chemotherapy may be given if octreotide does not control symptoms or the tumour grows despite treatment. Radiation is occasionally used either with Yttrium-90 DOTA octreotide/octreotate or from an external source (radiotherapy machine).

Pancreatic Cysts and Pseudocysts

Bile Duct Cancer Q & A

A cyst is a fluid collection. Fluid collections in and around the pancreas can be cysts or pseudocysts.

Inflammation of the pancreas (pancreatitis) can result in the formation of fluid collections called pseudocysts.

Unlike real cysts which are surrounded by a special layer of cells called epithelium, pseudocysts are surrounded by inflammatory tissue.

Although these fluid collections can cause serious complications such as infection, rupture or bleeding, they do not turn into cancer.

Broadly speaking pancreatic cysts are divided into:

Serous cysadenoma, which contain a thin fluid and are usually benign.

Mucinous cystadenomas, which contain mucus and have a risk of being cancerous or developing a cancer in the future.

Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms, which have a variable risk of developing into pancreatic cancer.

These affect the main pancreatic duct, the branch ducts or both.

Solid pseudopapillary tumours of the pancreas are rare and are usually benign.

Most of the pancreatic cysts are diagnosed on scans performed for other reasons. This could be an ultrasound, a computerised tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

If a pancreatic cyst is discovered, an endoscopic ultrasound is usually performed to diagnose the type of cyst.

This is an endoscopy test with an ultrasound attached to the endoscope. It allows close imaging of the pancreas as well as the ability to obtain fluid and cells for analysis.

This depends on the malignant potential of the cysts. Benign cysts are left alone, while cysts that have a malignant potential are removed surgically.

Intermediate cysts may be kept under surveillance with repeated scans.